In the automotive world, the V12 is sacred. It is the mechanical soul of Maranello, a screaming, naturally aspirated testament to performance engineering. But in 2025, the V12 is an endangered species, hunted by tightening emissions regulations and the forced march toward electrification. While most manufacturers are surrendering, downsizing to turbocharged V6s, though Porsche is also fighting back with a new W12 patent, Ferrari is attempting a “Hail Mary” pass to save the 12-cylinder engine.

A fascinating patent application from the European Patent Office (EP 24197835.2) reveals that Ferrari engineers are not just tweaking the fuel map; they are reinventing the most fundamental component of the internal combustion engine: the piston.

Forget everything you know about cylinder shapes. Ferrari is going “stadium.”

The core innovation: The “pill” and the twist

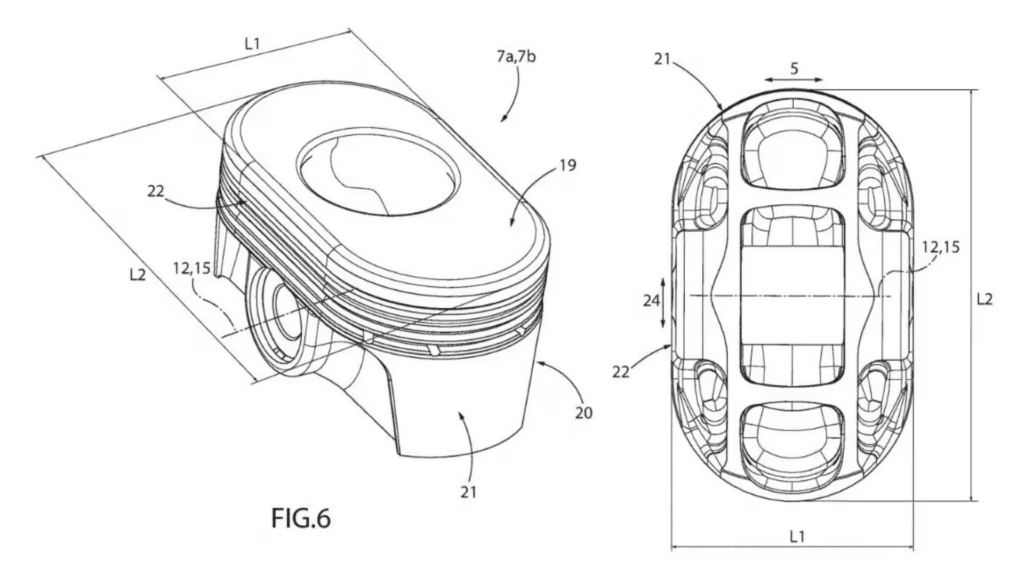

The internet is buzzing about “oval” pistons, but that’s not technically accurate. The patent describes a “stadium” or “pill” shape, geometrically defined as two parallel straight sides connected by two perfect semicircles.

But the shape isn’t the real genius here. It is the orientation.

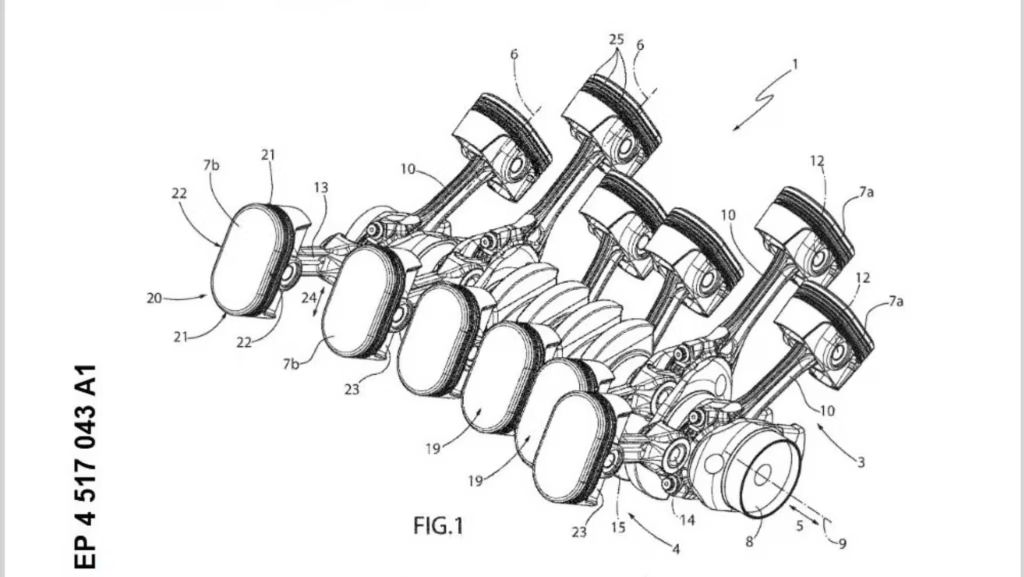

- The Concept: Ferrari intends to orient the long axis of the stadium piston perpendicular (at a 90-degree angle) to the crankshaft, effectively running “across” the engine.

- The Effect: Imagine looking down at a traditional V12 block. You see twelve big circles. Now, replace them with twelve slim rectangles standing on their ends. By turning the “wide” part of the piston sideways, the footprint of each cylinder along the length of the engine block shrinks dramatically.

Experimental engines like INNengine’s axial-cam “one-stroke” concept show that piston geometry is still an open frontier.

The mechanics: The “Zero-Stagger” solution

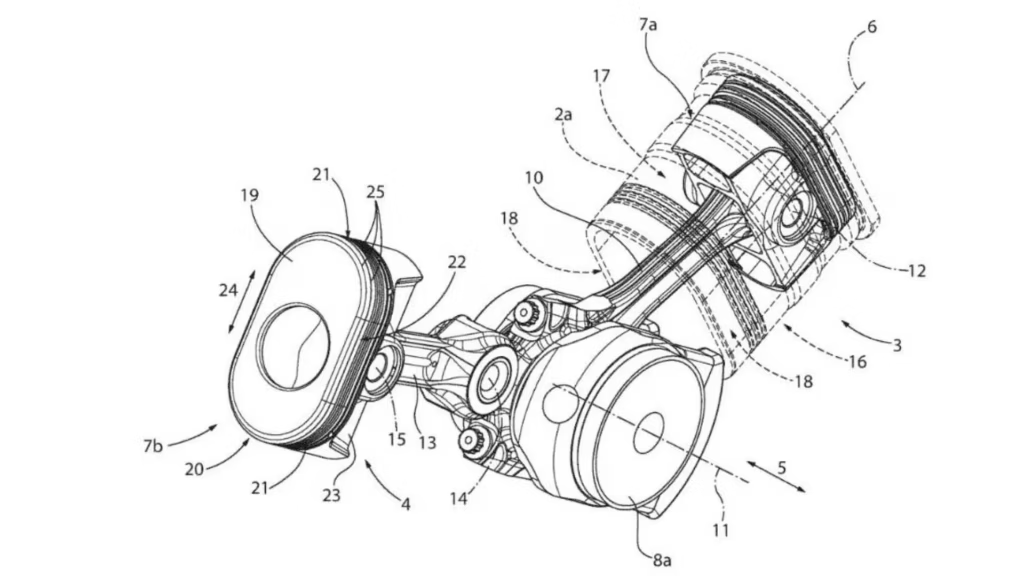

The sideways piston is only half the magic. The other half is hidden deep in the crankcase, involving a radical redesign of the connecting rods to solve a problem known as “stagger.”

In a standard V12, the cylinder banks are slightly offset because two connecting rods cannot occupy the same space on the crankshaft journal. This stagger adds roughly 20–30mm to the engine’s total length. Ferrari’s patent proposes a specific asymmetry to eliminate this:

- Parallel Rods: The connecting rods are perfectly parallel, allowing the cylinder banks to be perfectly aligned rather than staggered.

- The “Disconnected” Rod:

- The Right-Hand Rod connects to the crankshaft traditionally.

- The Left-Hand Rod is significantly shorter and utilizes a unique “kind of disconnected” assembly with its own individual pin.

The Result: This “Zero-Stagger” layout, combined with the slim stadium pistons, effectively creates a “flat-pack” V12. This significantly shortens the engine block, harking back to Ferrari’s heritage, specifically the compact 1.5-litre Colombo V12 of the 125 S, proving that a V12 does not have to be massive to be mighty.

Historical case study: The Honda “loophole”

You cannot talk about oval pistons without mentioning the elephant in the room: Honda. While the brand is currently focused on reviving icons like the 2026 Honda Prelude, ιn the late 1970s, Honda famously deployed oval pistons in the NR500 Grand Prix motorcycle. Many assume Ferrari is just copying Honda, but the motivations and mechanics are completely different.

The “Rule Breaker” Logic

Honda’s move was a legal workaround. Grand Prix rules limited engines to four combustion chambers. To compete with dominant two-strokes, Honda needed the valve area of a V8 but was legally restricted to a V4. Their solution was essentially a “V8 melted into a V4”: two pistons per bank conjoined into a single oval chamber. Unlike their modern track weapons, such as the Prelude GT500 HRC, the NR500 was an experiment that struggled to finish races.

| Feature | Honda NR500 (1979) | Ferrari Patent (2025) |

| Piston Orientation | Long axis PARALLEL to crankshaft (lengthwise). | Long axis PERPENDICULAR to crankshaft (transverse). |

| The Goal | “The Cheat”: Maximize valve area to simulate a V8. | “The Squeeze”: Minimize engine length for hybrid packaging. |

| Failure Point | Twisting: High RPM stress caused rods to twist and gudgeon pins to dislodge. | Solved: Modern materials and the new rod geometry aim to prevent this. |

| Outcome | Commercial Failure: The road-legal NR750 is a rare unicorn (only 20 made, valued at £115k+). | TBD: Aiming for mass production viability. |

Why now? The 3D printing advantage

If Honda could not make it reliable, why does Ferrari think they can? The answer lies in manufacturing technology.

- The 1970s Struggle: Honda had to machine complex oval shapes and internal galleries using traditional tooling. It was slow, expensive, and prone to imperfections.

- The Modern Solution: The source material emphasizes that Ferrari can use Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing). This makes creating the complex internal cooling channels and non-standard geometries an “absolute doddle.”

This manufacturing freedom also affects the cylinder head. While the patent hides the head design, the oval shape implies Ferrari may abandon their standard “three-in, two-out” valve arrangement (seen in their V8s), potentially increasing the number or size of valves significantly for better airflow.

Sidebar: The “weird piston” Hall of Fame

Ferrari’s design sits alongside a history of strange geometric experiments, most of which failed, where the circle succeeded.

- Dome Pistons: Convex (curved outward) pistons are typically found in older diesel engines or those requiring high compression ratios.

- The “Twingle”: A strange configuration where a single connecting rod splits to drive two pistons that share a single combustion chamber.

- Square Pistons (The Horsack Engine): An attempt to combine piston and rotary mechanics. It failed because square corners are stress traps, and creating a piston ring that can seal a sharp 90-degree corner is nearly impossible.

- The F1 V10 (Early 2000s): While circular, these were extreme in their own right. With massive bores and ultra-short strokes, they allowed engines to rev past 20,000 RPM, producing 900 horsepower without a turbocharger.

The physics: Energy and efficiency

Does a pill-shaped piston actually work better? Here is the breakdown of the physics involved.

Thermal vs. Kinetic Energy

- The Surface Area Problem: By stretching the piston into a stadium shape, Ferrari increases the Surface-Area-to-Volume ratio. More surface area means more heat is absorbed into the metal block (thermal loss) rather than pushing the piston down.

- The Counter-Balance: Ferrari’s design aims to reduce friction. The “disconnected” rod assembly removes half the main rod bearings on the crank. The patent also mentions “large recesses” on the piston skirts to minimize contact with the cylinder wall.

- Net Efficiency: While thermal losses increase slightly, the reduction in mechanical friction helps balance the equation.

Biofuel Compatibility

This engine is almost certainly designed to run on E-Fuels (synthetic fuel made from captured CO2). By 2035, the EU may ban fossil fuels, but not internal combustion itself if the fuel is carbon-neutral. This “Stadium V12” combined with E-Fuels, is Ferrari’s ticket to selling combustion cars in the 2030s.

The survival strategy

Ferrari is not doing this for horsepower. They are doing it for packaging.

Future supercars must be hybrids. But batteries and electric motors take up space. If you add a hybrid system to a standard V12, the car becomes too long and handles poorly. By using “Stadium Pistons” and the “Zero-Stagger” rod layout to shrink the engine length, Ferrari creates a physical “gap” in the chassis, just enough room to sandwich an electric motor without ruining the car’s perfect balance.

It is a complex, expensive solution. But if it keeps the V12 alive for another generation, every car enthusiast should be rooting for it. While Ferrari engineers the inside, who designs the outside? Read about Ferrari’s legendary design partner in our coverage of the Infinix & Pininfarina Partnership.